How a space colony simulator teaches players to be good founders

Note: this post is based on a tweetstorm from when I was playing a lot of Rimworld

I love real-time strategy and simulator games. I have sunk countless hours into Age of Empires and Civilization, plus a decent number into Stronghold. In a similar vein, I played a lot of Roller Coaster Tycoon and, if you can believe it, Sim Golf.

One recent game that has made its way into my personal pantheon is RimWorld. For the uninitiated, RimWorld is like Sim City or Civilization, but on a smaller scale; you control a colony (initially three people) of crash-landed space travelers try to survive.

You start with a few key resources. The goal is to build up your colony by harvesting additional resources and advancing technologically. One way to win is to build a ship and escape the planet, but there are others, and surviving in perpetuity is also fine. The only way to lose the game is for all your colonists to die.

After playing a few games to completion - each several hours - I started to see parallels to startups. After playing a few more games, I couldn’t stop seeing them.

Parallel One: Crew

Before the game starts, you pick three colonists to start your colony. Every colonist has their (randomly generated) strengths and weaknesses in various skills. The skills of the colonists you select must be both complementary and sufficient. In other words, your colonists need to split up work effectively and cover the bare minimum of skills to survive.

If the parallel stopped here, it would still be worth mentioning. Selecting a founding team well is absolutely critical. If you do it wrong, you’re probably dead, and the only real way to get a new founding team is to start the game/company over.

As it turns out, the parallel runs much deeper; the skills that your founding colonists need line up eerily well with the skills founders need. Specifically:

- Growing plants = Sales (growing revenue)

- Researching technologies = Engineering (creating tech)

- Building, cooking, cleaning, etc = Operations (everything else that makes a company run)

The classic founding team is one person doing sales and one person building the product. Depending on the company, there may be a third person for that Operations bucket, or the other two founders may split those duties.

Parallel Two: Landing Site

After you choose your crew, the game shows you a map of the world and asks you to choose a place to have your crew crash-land. (Kind of ironic, no?) Clicking on a spot shows you information like the biome, the geology, the minimum and maximum temperatures, etc. The map also shows you how close your site is to competing colonies.

Here, the game’s order of operations exactly parallels a startup’s; first you pick your team, then you pick you market - the area (i.e. industry/vertical) in which your team will work.

You want to pick a landing site (market) that will allow you to grow plants (grow revenue) easily. There are other considerations, but they aren’t as metaphorically resonant.

One anti-parallel here is proximity to competitors. The game will warn you if you pick a landing site that’s too close to a competing colony. In startups, you usually don’t have to worry about competitors until much later on. More on that later.

Parallel Three: Initial Colony

Now that you have your crew and your landing site, you’re ready to start the actual gameplay - building your colony.

Laying out the initial foundations of your colony correctly is crucial. While your colonists crash-land with some food to start, they will quickly starve if your colony can’t produce plants to cook into meals, so clearing soil and planting crops is top priority. They will become mutinously unhappy without shelter, so building a house with heat and beds (and a stove for cooking!) is next. Once you have the basics working, you can move on to collecting other materials (wood, steel) and researching technologies.

The biggest danger here is trying to do too many things at once. If you set tasks for growing, building, collecting, and researching all at the beginning of the game, you probably won’t finish any of them by the time your initial food runs out. Even though you have to collect other resources and research technologies to win the game, you need to wait patiently until you have the basics nailed.

Extending the parallel of food as revenue, the same logic applies with startups. As Paul Graham notes, you should become default alive basically as soon as possible. Your seed capital (the food you crash-landed with) allows you to become default alive if you focus well.

I find myself particularly susceptible to excess ambition when building a colony. I have lost several games because I planned too far ahead, building a massive house to store my future legions of colonists or mining precious metals in order to build fancy tech. I am determined to remember the lesson of focus from RimWorld when founding my next company.

Parallel Four: Strategy

Strategy here revolves around the tech tree - the different technologies you can research.

To build the spaceship and escape the planet, there are five technologies you must research. However, each of the five has several predecessors on the tree. Just like humans had to invent writing before inventing the printing press, your colonists must research the basics before researching the advanced.

In addition to the five end-stage technologies and their predecessors, there are other technologies on the tree that don’t directly help you build the spaceship. For example, you can research advanced weaponry. Advanced weaponry helps you defend your colony from hostile tribes so your colony can survive long enough to build the spaceship, but it doesn’t directly help you build the spaceship. Some such technologies are practically requirements - it’s hard to power your colony without researching batteries, for example - but most are truly optional. With the proper strategy, you spend as little time on such support technologies as possible and focus on spaceship technologies; without proper strategy, you chase down every support technology like a shiny new object, drawing out or even endangering your path to victory.

In much the same way, a successful startup must have a strategy. Strategy tells you what focus on and, more importantly, what not to focus on. A young company has many possible paths to success, but it can’t pursue all of them a little bit at once; it only has the time and resources to pursue one of them full bore. Everything the company does should either be in direct pursuit of the strategy (spaceship technologies) or should clearly enable the strategy (certain support technologies).

Parallel Five: Comparative Advantage

RimWorld has an astounding array of items. For example, there are 58 different types of leather.

Beyond food, you don’t need an incredible variety of materials - steel, gold, uranium - but some of the materials you need are hard to find or produce. To compensate, you can sell goods for silver (or mine it directly) and purchase goods you can’t collect or produce yourself.

As a novice player, I rarely took advantage of trading. It took me ages to collect enough of certain raw materials, and there were others my area of the map simply did not have. It’s hard to be an autarky.

Over time, I learned the immense value of trade. I learned to focus on one or two goods I could tune my colony to produce en masse, then sell them and buy anything else I might need with the proceeds.

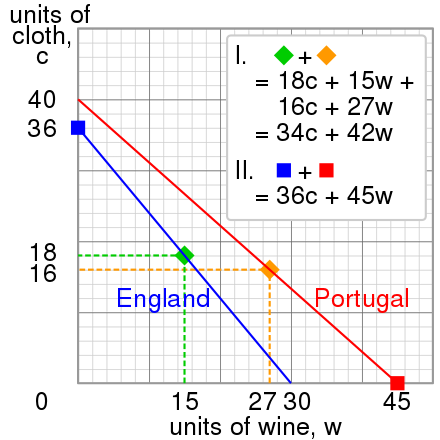

My lesson wasn’t in the value of trade per se - I had traded a bit even in my first game. No, the concept I learned to love is comparative advantage. In short, comparative advantage says you should produce only the thing you are best at producing and trade for the rest, even if you are better than your trading partners at producing the things you’re receiving from them. David Ricardo, the economist who first conceptualized the theory, used the example of Portugal and England producing or trading cloth and wine:

Startups encounter the same dynamic in two guises. The first guise is the classic choice between buy and build. For example, if your web app needs a billing feature, do you integrate with an existing billing tool, or do you build the feature yourself? Because startups are scrappy, they err on the side of build. However, comparative advantage says to err on the side of buy - use the time to build more of the thing the company is best at.

The second guise is delegation. Most founders I know have multiple strengths and can wear a wide array of hats. You need that in the beginning when it’s just you and your cofounders - when you have no trading partners (i.e. employees). Once you have employees, though, you have to delegate to them and focus on the thing you are best at. Burnout aside, not delegating means the company is a whole is “poorer” (i.e. less productive) than it could be, by the logic of comparative advantage.

Parallel Six: Competition

RimWorld throws raiders at your colony from the start, but they are never the biggest threat early on; the biggest danger is from internal dysfunction and running out of food. It’s only much later, once you start construction of your spaceship, that raids intensify and become potentially game-ending.

In much the same fashion, competition is almost never the reason startups die. Instead, the immediate cause of death is either:

- The founders gave up

- The company ran out of money

Sure, once a company reaches a certain size, a bigger competitor may take action, but the vast majority of startups never reach that certain size. If competitors are the biggest threat to your existence, you’re in a good place.

Parallel Seven: Victory

The main way to win in RimWorld is to build the spaceship and take off. The game doesn’t exactly tell you that’s how you win, but the story makes the most sense if it ends with the crash-landed colonists returning to space. Plus, the tech tree ends with the spaceship technologies, implying there is nothing more important beyond. (There are other, more obscure ways to win, but we won’t discuss them here.)

However, you don’t lose by simply keeping your colony alive. There is no countdown, your colonists don’t complain if you never build the spaceship, and the only way to actually lose is if all your colonists die.

Here, RimWorld mirrors startups in an almost uncomfortable way. The typical startup takes venture capital money in exchange for the promise to grow fast and eventually IPO or sell to an acquirer - the “rocket ship” path. These are the companies you read about in TechCrunch and that have movies made about them.

Some companies, though, grow to a certain size and then plateau; they make a product clients love, they provide quality jobs to their employees, but they don’t make substantial returns for their investors. They don’t appear in the tech press. The spotlight doesn’t shine on them. The startup game doesn’t recognize their victory.

Conclusion

I like RimWorld. Like all good games, it is easy to learn but difficult to master. It provides the satisfaction of building something without burdening you with real-world risk and consequences.

For RimWorld players interested in startups, I hope you can find value in the expertise you have built. For entrepreneurs interested in RimWorld, I believe you will find your own lessons in the hours you play. For RimWorld players who are also entrepreneurs, I suspect you will see my parallels in any future rounds of either pursuit.

Startups are expensive, RimWorld is cheap - so get playing!